Are Horses Ruminants?

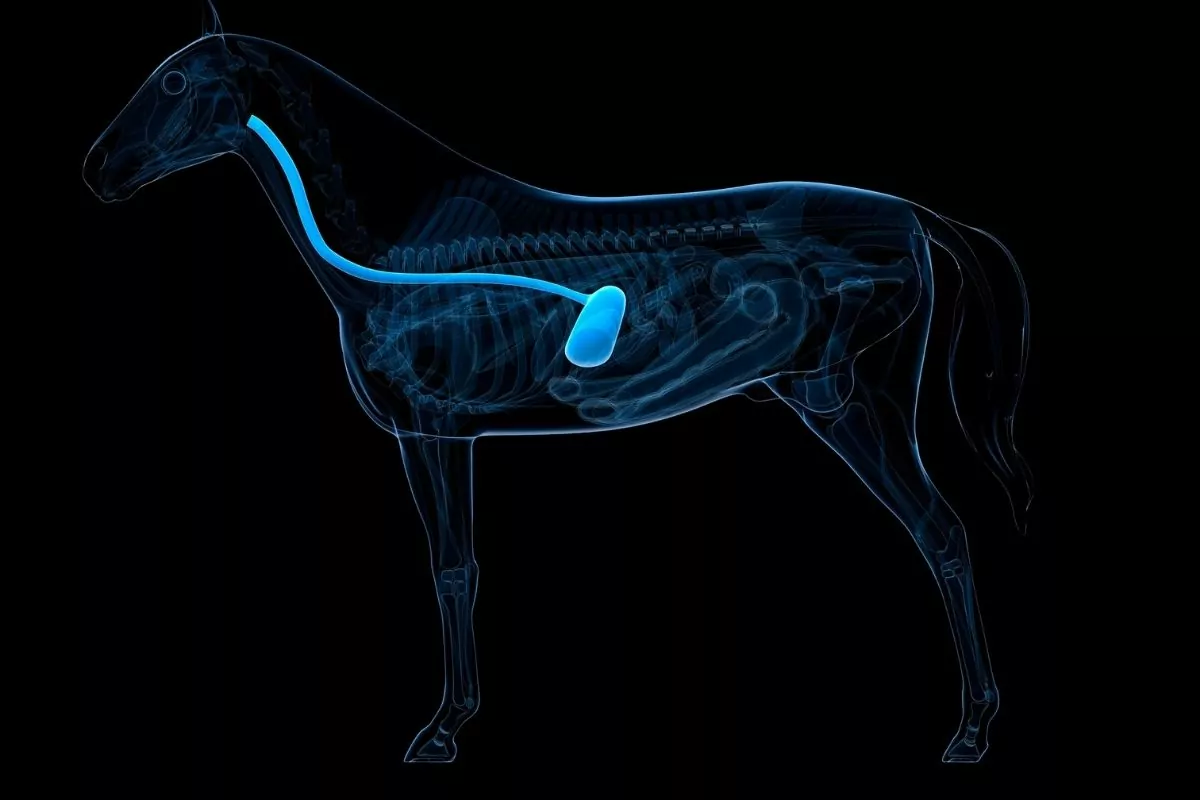

Are horses ruminants? How many stomachs does a horse have? These are questions you may be asking yourself. Horses are herbivores, and their stomachs have only one chamber. Therefore, they lack a multi-compartment stomach like cattle yet can eat and digest grass. The cecum and colon are sections of the large intestine and function similarly to the rumen in the cow.

How Many Stomachs Does a Horse Have?

You may believe that all herbivores, including horses, have the same digestive system. However, a horse’s stomach contains only one chamber. Therefore, their non-ruminant digestive system has substantially more complications than other non-ruminants.

An equine’s digestive system includes a stomach’s small and large intestines. The food enters the mouth, and the waste exits through the anus. The hindgut comprises 65% of the overall digestive tract. The caecum is a big junction with a bag shape of the small and large intestines.

Fermentation occurs in the caecum and creates vital nutrients such as amino acids, lactic acid, and proteins. Without proper care, hindgut can be a big issue for horses. Caecum, large colon, and tiny colon microorganisms are pH sensitive, and fluctuations in acidity can cause significant internal injury to horses, such as colic.

An abrupt diet change or even overfeeding can cause colic in horses. Unchecked grain intake causes a sudden change in the hindgut’s sugar and starch levels that remain after digestion. The upper stomach absorbs most sugars and starches when feeding the horse quick meals. If the horse overeats, the insoluble carbohydrates, sugars, and starch can spill into the hindgut.

The microorganisms and bacteria present switch from fiber-fermenting to starch-fermentation. This abrupt change in fermentation produces excess gas and lactic acid, lowering the pH and causing colic and, in some cases, laminitis.

How Long Does It Take a Horse to Digest Food?

You’ve undoubtedly heard some surprising figures concerning the horse’s digestive system. If you stretch the entire digestive tract, it would be around 100 feet (30.5 meters) long. The horse’s stomach is small compared to its size, and although digestion begins here, food will not stay in the stomach for long.

After entering the stomach, food enters the small intestine, absorbing most nutrients. Any food item not digested in the small intestine travels onto the hindgut (the cecum and large intestine), where microbial fermentation occurs.

Feed matter can linger here for many hours as the bacteria that naturally fill the hind colon ferment and break down the plant fiber, getting the possible nutrition from the meal. Problems can emerge when the horse eats too fast, doesn’t chew their feed correctly, or you feed them too much at one time.

These conditions may cause excessive fermentation and gas, which may not result in healthy digestive function.”As a rule of thumb, it takes 24 hours for food to pass entirely through the horse’s digestive system.

The feed only takes about 1-1/2 hours to pass through the upper intestine; the rest of the time, it’s moving through the hindgut. This is because the equine digestive process depends on a healthy population of helpful microbes.

It can’t function effectively without these “good bugs.” They help maintain the pH level of the intestine, which prevents dangerous microbes from proliferating.

They also create antibiotic-like compounds and specific enzymes that kill many dangerous bacteria, viruses, and fungi. Beneficial microbes also neutralize bacterial poisons. The horse and these beneficial microorganisms are symbiotic. The horse needs them for digestion, and the bacteria thrive inside their “host.”

Can Horses Digest Cellulose?

Horses’ stomachs and small intestines work similarly to other monogastric animals. First, the small bowel degrades and absorbs the soluble carbohydrates as monosaccharides. Then, carbohydrates like cellulose, hemicellulose, starch, and other soluble carbohydrates move into the large intestine, fermented.

Horses and other hindgut fermenters have a similar fermentation system to the rumen. The fermentation process in the hindgut is quite identical to that in ruminants’ forestomachs.

To survive as herbivores, horses produce large amounts of volatile fatty acids, absorbed through the cecal and intestinal epithelium and transported throughout the body. Unlike ruminants, the large intestine of horses does not allow for significant amino acid absorption; hence a large amount of microbial protein is lost.

How Long is a Horse Intestine?

The small horse intestine is nearly 70 feet (21.3 meters) long and has three segments. The first section is the duodenum. It starts at the stomach and extends 3-4 feet (0.9-1.2 meters). The second component is the jejunum. This is the most extended portion and compromises the majority of the small intestine. The final segment is the ileum, which includes the small intestine’s remaining 1-2 feet (0.3-0.6 meters).

The ileum links to the cecum, the first section of the large intestine, and is analogous to the human appendix. Many disorders can occur in the small intestine and produce colic.

What Kind of Digestive System Does a Horse Have?

Horses are non-ruminant animals. You can classify animals based on physiological and physical characteristics. For example, herbivores are classed as ruminant or non-ruminant by their digestive mechanism. A ruminant animal, such as a cow or goat, has a stomach that works in four processes: regurgitation, remastication, re-salivation, and re-swallowing.

Their stomach contains four compartments where the process occurs. How many stomachs does a horse have?

Non-ruminant animals, like humans and horses, have a more straightforward stomach structure with a single compartment and a typical digestion process where protein digestion takes place in one step. The stomach anatomy of ruminants and non-ruminants differs.

Horses should never be fed cattle feed. Horses’ stomachs require different nutrients than cattle’s. Moreover, the digestive systems of ruminants and non-ruminants require other ingredients. The horse’s stomach has digestive enzymes and hydrochloric acid, just like ours, and only enzymatic digestion breaks down grain.

You can feed cattle with low-quality plants or fibrous nutrients that disintegrate quickly in their four-compartment stomach. Cattle feed provides minerals beneficial to cattle but not beneficial to horses. Cattle feed is high in non-protein nitrogen and contains urea.

Cattle rumen microorganisms can convert nitrogen into protein, which they need to meet their amino acid demands. The urea transforms into ammonia in the stomach, and the small intestine absorbs it. If the horse consumes a large amount of urea, it may be poisonous and cause death.

Equine digestion has several advantages and disadvantages over ruminant digestion. Horses can run faster than ruminants because their stomachs are smaller. Horses are not obese because their digestive system processes food faster than ruminants. Unlike cows, horses’ digestive systems can quickly consume an enormous feed.

Ruminants’ four-compartment stomachs aid in protein digestion. The stomach stores the food. Thus, you do not need to feed them frequently. However, horses only have one stomach compartment. Therefore, you must provide them with small meals often. Both ruminants and non-ruminants have sensitive bacteria and microorganisms.

The horse’s caretaker must know their outward and internal characteristics. For example, horses cannot regurgitate like cattle, so don’t feed them moldy food or hay. Such hay will seriously harm the stomach.

Interesting Facts About Horse Digestion

- Non-ruminant herbivores, including horses’ digestive systems, blend monogastric digestive processes and ruminal animals like cows. You can’t feed horses like other household animals, and you should give them modest meals frequently. Many astounding facts will enable us to understand the horse digesting system better.

- At a time, horses may chew the meal just on one side of their mouth. However, if you allow them to eat lots of plant material, horses can make a lot of salivae sufficient for chewing. As they chew the feed, saliva helps wet the food particles, making it easy to gulp. In addition, the saliva in the stomach neutralizes the hydrochloric acid that the stomach produces.

- Horses cannot vomit as a horse’s esophagus operates only in one direction; it enables the food to move from the throat to the stomach. As a result, the feed can move down, but it cannot travel upwards. Improper digestion can result in the fast production of colic, a primary cause of death.

- The horse’s stomach can store just around 2 gallons (7.6 liters), and the feed only remains for 15 minutes inside the stomach, then travels into the small intestine.

- The acid that the horse’s stomach produces might attack the cells in the stomach lining if the horse is hungry for too long. This results in ulcers inside the horse’s belly; hence feeding them with small meals is required.

- The small intestine enzymes break down the starch into glucose, lipids into fatty acids, and protein into amino acids. The small intestine is the principal organ for digesting and absorption in horses.

- The caecum and large intestine walls are full of bacteria and other microorganisms. This microbial population ferments the foodstuff, a process called microbial digestion.

- Horses don’t have gallbladders, although they can eat a lot of fat. So the feed enters and exits the caecum top-only.

- If your horse does not get enough water to drink, the caecum is at risk for impaction colic. Changes in the horse’s diet should be made gradually as the bacteria in the small intestine cannot ferment new foods adequately, causing colic. In addition, the horse cannot absorb the dietary fiber lignin found in ripe hay.

- The amount and rate of feed intake affect digestion and nutrient absorption. Increasing the horse’s intake slows down digestion and absorption in the small intestine. You can hear gut noises as food passes through the digestive tract. The absence of these noises indicates an intestinal obstruction. The equine digestive process takes 36-72 hours from mouth to anus. What if you stretch the horse’s digestive tract to 100 feet (30.48 meters)?

The Parts of the Horse Digestive System and Their Functions

Mouth

Horses eat with their lips, tongue, and teeth. Horses’ lips are very tactile when eating feed. Many of us have seen powdered vitamins or pellets in a lovely little pile at the feed bin bottle. Feeds are combined with saliva in the mouth to form a wet bolus. The parotid, submaxillary, and sublingual glands all generate saliva.

Horses produce 5.3-21.1 gallons (20-80 liters) of saliva daily. Salvia includes bicarbonate, which preserves amino acids in the stomach’s acid. In addition, saliva contains amylase, which aids in carbohydrate breakdown. Females have 36 teeth, and males have 40 teeth). No wolf teeth because not all horses have them.

The horse’s upper jaw is more comprehensive than its lower jaw, allowing for a complicated chewing motion. The horse’s chewing action is sweeping, combining lateral (forward and backward) and vertical movements.

This grinds the feed and mixes it with saliva to start the digestive process. The texture of the meal affects the chewing rate (jaw sweeps) and swallowing.

An average horse grazes 60,000 jaw sweeps per day. This amount will reduce when the horse keeps stable and feeds heavily. Larger horses take longer and require more jaw sweeps to masticate their meal adequately. Ponies take even longer to devour their meal.

Horses chew fibrous feeds like hay or pasture with their jaws open wide. This is why pastured horses rarely grow sharp teeth. Grains are digested in a shorter sweep, not reaching the teeth’ outside edge. Large amounts of grain affect the horse’s chewing movement and wear the teeth unevenly. As a result, the outer edge of the teeth will develop hooks or sharp edges.

Improper floating or rasping adversely influences Intake rate, chewing efficiency, hunger, and disposition. In addition, the bolus (feed and salvia) might lodge in the esophagus and induce choking.

Oesophagus

A mature horse’s esophagus is 4.9 feet (1.5 meters) long via a muscular tube from the lips to the stomach. Because the horse’s esophagus is lengthy and has little reflux capacity, significant bits of feed like carrots might get stuck inside and cause choking.

That’s why keeping horses’ teeth clean helps them chew their grain correctly and prevents them from “bolting” it down without chewing it. Likewise, adding chaff to a horse’s feed or placing a brick or a big stone in the feed bin will decrease the horse’s intake and reduce the chance of choking.

Stomach

The horse’s stomach is small compared to its body size, holding only 10% of the digestive system’s capacity of 2.3-3.9 gallons (9-15 liters). As a result, horses naturally eat tiny amounts of roughages frequently. Domestication changed all of this. To fit our lifestyle, horses now eat considerable amounts of grain feed once or twice daily.

This damages the horse’s digestive system and wellbeing. The benefits of providing small meals frequently (assimilating natural grazing) are the best option. Pepsin (a protein-digesting enzyme) and hydrochloric acid help break down solid particles in the stomach. The rate of feed transit in the stomach varies depending on how you feed the horse.

A hearty supper can reduce passage time to as little as 15 minutes. Fasting horses’ stomachs require 24 hours to cleanse. It’s long been a challenge first to feed a horse grain or hay. Due to their density, Grains tend to stay in the stomach longer; however, feeding either first has not been shown.

To slow down rapid eaters, you can add trash to the meal to bulk it out. A horse should also drink water before or after a meal. If you let the horse consume dry feed, it will typically drink a bit as it eats. The best advice is always to provide clean water.

Succus caucus, fundic, and pyloric regions make up the stomach. Both in structure and function. You can find the saccus caucus at the stomach and esophageal entrances. As soon as food enters the stomach, hydrochloric acid and pepsin, a protein-digesting enzyme, works on it.

As a result, the feed (especially if it’s mostly grass) already contains soluble carbohydrates for absorption and lactic acid fermentation. In normal circumstances, as hydrochloric acid combines with stomach contents, the pH drops, and fermentation slows.

Without it, the generally non-distensible, fixed-volume stomach quickly fills with gas, causing gastric colic or, in extreme cases, a perforated stomach lining. The fundic area follows the feed through the stomach. When the pH drops to 5.4, fermentation stops. Pepsin and stomach acid start the breakdown of lipids and proteins (amino acids).

The pyloric area connects the stomach to the small intestine. The pH decreases to 2.6, killing all fermentable Lacto-bacteria. This area’s proteolytic activity is 15-20 times that of the fundic region. Due to new feeding procedures, horses’ stomachs remain nearly empty for long periods. As a result, the stomach acid interacts with feed and saliva.

Acid damages the squamous cells in the saccus caucus region of the horse’s stomach when it is empty. This causes stomach ulcers. Studies suggest that almost 80% of thoroughbreds develop stomach ulcers.

Stomach ulcers affect the mood, appetite, and performance of the horse. Therefore, giving horses more roughage, small frequent meals, and allowing them to graze would significantly minimize the frequency and severity of stomach ulcers.

Small Intestine

The digester enters the small intestine. The small intestine is 28% of the horse’s digestive tract. The duodenum, jejunum, and ileum make up the small intestine. Horse saliva contains little amylase, and most horses’ stomachs do not digest much.

The small and large intestines do most of the work. Although the colon produces some enzymes, the pancreas produces the most.

The small intestine digestive processes (enzymatic digestion of proteins, lipids, carbohydrates, and sugars) are similar to other monogastric mammals, although the chyme (food mix) enzyme activity, particularly amylase, is lower.

This digestive process has various components. Pancreatic enzymes help break down food into amino acids; lipases and bile from the liver help emulsify (break down) fats and suspend them in water. Because the horse has no gall bladder, bile constantly pours into the small intestine.

After the digestion of the feed takes place, the small intestine walls absorb it, and the bloodstream takes it away to whatever cells need the nutrients. The small intestine handles 30-60% of carbohydrate digestion and absorption and nearly all amino acid absorption.

The small intestine absorbs fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K and minerals like calcium and phosphorus. Micronization, for example, changes the structure of carbohydrates in feed, increasing small intestine digestibility to over 90%. This eases the strain on the large intestine and minimizes the risk of colic, laminitis, and acidosis.

Food passes through the small intestine in 30-60 minutes, as most digesta flows at around 11.8 inches (30 centimeters) per minute. However, feed passes through the small intestine in 3-4 hours. This is because the enzymes have less time to work as the digesta passes through the small intestine.

Adding oil to a horse’s diet slows feed passage through the small intestine, allowing digestive enzymes more time to absorb carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, enhancing total tract digestibility and efficiency. However, the toxic feed can cause colic or death in horses.

Instead of being detoxified in the cow’s rumen by bacteria, harmful substances consumed by horses enter the intestine, and the bloodstream absorbs them before they undergo detoxification. So don’t feed horses moldy or rotten grain. Urea is a protein-making feed additive for cattle.

Horses do not use this feed additive because it is absorbed in the small intestine before reaching the cecum. Although urea is hazardous to horses, it is safe to use in most cattle feeds. The horse cannot use the microbial protein that the large intestine produces.

Foals, lactating mares, and possibly hard-working horses require high-quality protein that can be broken down and absorbed in the small intestine. In practice, this means improving the feed’s quality rather than increasing the crude protein content.

This may entail ensuring adequate quantities of critical amino acids like lysine, methionine, and threonine to suit the horse’s needs.

Hindgut

The caecum, large (or ascending colon), small colon, rectum, and anus make up the hindgut or large intestine. Much of the digestion takes place work here. The hindgut is around 22.9 feet (7 meters) long and has a volume of 36.9-39.6 gallons (140-150 liters). The hindgut’s digestion is mostly microbial, not enzymatic.

A billion symbiotic bacteria break down plant fibers and undigested starches into simpler chemicals called volatile fatty acids (VFA’s) that the gut wall could absorb during digestion.

The horse’s digestive tract is not as good in digesting grass products high in crude fiber, low in protein, and poor in carbs, starch, and fat. Nevertheless, they outperform humans and pigs! And equids have overcome these drawbacks by grazing massive amounts of forage daily.

Caecum

The caecum is a 3.9 feet (1.2 meters) blind sack that holds 7.4-9.5 gallons (28-36 liters) of feed and liquids. Inoculation vat similar to the rumen in a cow. The microorganisms break down a non-digested meal, especially fibrous foods like hay or pasture: the caecum’s unusual design entrance and exit at the organ’s apex.

The stream enters at the top, mixes throughout, and exits at the top. This design causes issues when an animal eats a lot of dry feed without enough water or switches diets quickly. Both can cause caecum compaction and pain (colic). A caecum’s microbial community is selective in what meals it can digest.

It can take 2-3 weeks for the caecum’s bacteria population to acclimatize to a new diet and operate normally. That is why you should introduce new feeds gradually over 7-14 days. The meal will stay in the caecum for around seven hours, allowing bacteria to start fermenting it.

Bacteria produce vitamin K, B vitamins, proteins, and fatty acids. Vitamins and fatty acids are absorbed, but protein is not.

Big Colon

The large colon (right and left ventral colons) is 9.8-11.5 feet (3-3.5 meters ) long and holds 22.7 gallons (86 liters). Most nutrients that microbial digestion (fermentation) generate are absorbed here, including B vitamins, trace minerals, and phosphorus. The ventral colons are “sacculated,” like a series of pouches.

This design facilitates the digestion of large amounts of fibrous materials but increases the risk of colic. Fermentation of the feed causes the pouches to twist and fill with gas. The meal can arrive in seven hours and stay for 48-65 hours.

Rectum, Small Colon

The little colon is the same length as the large colons but only 3.9 inches (10 centimeters) in diameter. As a result, the horse cannot digest or utilize what is left. Instead, the small colon’s main job is to return surplus moisture to the body. Fecal balls occur as a result. The anus transports these indigestible fecal pellets through the rectum.

Digestive Tightrope

Under standard settings, the equine gastrointestinal tract works well. However, because the equine gut is so delicate and easily upset, colic is the leading cause of equine death. This can cause colic or at least a diminished digestive efficiency of the meal.

Stress, long-distance travel, illness, injury, antibiotics, weaned foals, or high-performance horses fed significant amounts of grain can disrupt the microbiota. Therefore, we must respect the horse hindgut and check our horses’ food and general condition.

Small frequent meals, similar to their regular grazing habits, will considerably lower the incidence of gastrointestinal issues. That will allow you to enjoy your horse.

Conclusion

From our discussion, how many stomachs does a horse have? We can conclude that a horse has a stomach with a single compartment. Its digestive system is non-ruminant, although it is more complicated than other non-ruminant animals. Several parts are essential in the digestive system of the horse. These include the mouth, esophagus, stomach, and others.

Domestic horse breeds include the hot-blooded, cold-blooded, or warm-blooded. Hot-blooded horses deal with speed and endurance. Cold-blooded horses are suitable for slow, laborious work like pulling wagons. Warm-blooded horses are crossbred cold-blooded and hot-blooded horses that are best for riding.

Humans and horses get along well. They are helpful in sports and non-sporting activities such as agriculture, entertainment, and rehabilitation. Horses have a long history, used in many ancient wars. Before the engine, the only way to travel vast distances was by horseback.

Humans domesticate horses and feed, shelter, and water them. Horse owners even see veterinarians for their horses’ health. Horses are friendly and fun to have around you.