Defining Mastitis in Dogs

Mastitis in dogs refers to inflammation of the mammary glands. It is most commonly seen in the female dog but can also occur in male dogs. Still, it is most commonly seen in lactating, pregnant, or postpartum bitches.

There are two types of mastitis, the first being galactostasis (meaning milk not flowing), which often occurs in pregnant bitches close to whelping when milk is building up in the mammary glands, but there are no puppies to empty it.

This can cause swelling and pain but is usually transitory, and since there is no infection does not require antibiotics. Galactostasis may still require treatment.

The second type of mastitis is septic mastitis (meaning infection). This can be acute (sudden) or chronic (last a long time). The infection is most commonly from bacteria, but rarely fungal infections can also occur. Dog mastitis is less common than in other species, but it can be severe and even life-threatening if left untreated.

It can be challenging to determine the difference between the two types of mastitis. Hence, it is essential for you to take your dog to the veterinarian and have them examined so that treatment can be instigated in a timely manner.

What Causes Mastitis?

Infectious mastitis occurs when bacteria (and rarely fungi) enter the mammary gland and set up an infection. The bacteria’s source is most commonly from the skin, from the outside environment, or from bacteria in the blood. Mastitis can occur at the same time as metritis (inflammation of the uterus).

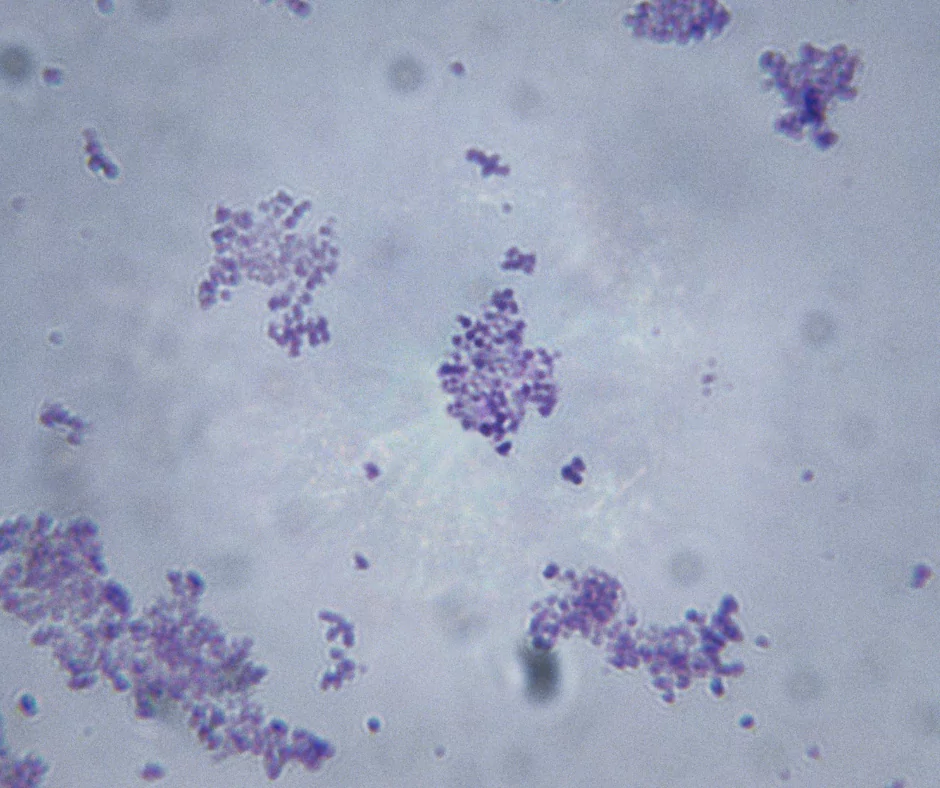

The most common bacterial species causing mastitis are Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus sp., and Streptococcus sp.

In a lactating bitch, infectious agents can often enter via a damaged nipple or mammary gland, either from cracking or scratches from puppy nails or teeth or from physical damage, hitting the engorged tissue against the whelping box, for example.

A whelping box that isn’t cleaned regularly or has damage such as splintered wood or exposed nails poses a significant threat to mastitis development.

In a non-lactating dog, an infection can occur secondary to an infection in another part of the body migrating through the blood or from mammary gland cancer.

If you notice signs of mastitis in your dog, even if they aren’t pregnant or lactating, it is crucial to have them examined by your veterinarian.

Early Signs and Risk Management of Mastitis in Canines

In mild cases, the first signs of mastitis can be subtle; mild mammary discomfort and heat, galactostasis (milk not flowing), inflammation of the skin, and presence of a mass inside the mammary gland are often the earliest signs.

The milk is often red or brown due to the presence of red and white blood cells.

As cases become more moderate, you will begin to notice pain, reluctance to nurse pups, not wanting to lie down (painful), not wanting to eat, and being lethargic. You may see your puppy’s weight gain stall as the dam feeds them less. A marked fever may be one of the first signs of a moderate infection.

Advanced or severe cases can present in septic shock, which involves a high fever, or in extreme cases, the body temperature can actually be low. You may also see abscesses on the mammary gland or tissue dying away (necrosis).

If you notice any mastitis signs, it is essential you get your dog treated ASAP as a mild case can turn into a severe case very suddenly and become life-threatening.

The Diagnosis of Mastitis in Dogs

A diagnosis can only be made by your veterinarian. Most commonly, a diagnosis can be made on a physical exam and history collected from you, the owner.

Galactostasis will usually not require further work up, but infectious mastitis might.

Common diagnostic tests include collecting a milk sample aseptically and sending it off to be cultured to see what type of bacteria are grown. Once the bacteria type is established, the lab will then determine how sensitive the bacteria are to different antibiotics. This test is called a culture and sensitivity test and can help your veterinarian determine the best type of antibiotic to choose to treat your dog.

An ultrasound could also be used to look inside the mammary gland to look for signs of abscess and assess the extent of damage to the gland, and monitor response to treatment.

Depending on how severe the mastitis is, other tests may be performed, such as blood work to determine your dog’s health and see if there is any systemic involvement. In a non-lactating or non-pregnant dog, further investigation may be required to determine where the infection came from.

Treating Mastitis

The treatment for mastitis in dogs varies depending on the severity. In mild cases, antibiotics and pain relief are the mainstays of treatment, therapy is usually begun right away, but the antibiotic choice may change if the culture and sensitivity come back to say that the antibiotic chosen initially wasn’t the best option.

Warm compress with towels and gentle stripping (milking) of the affected gland can prevent abscesses from forming.

Protecting the affected gland from trauma can be helpful. Using a t-shirt or bandage can prevent it from being knocked. Clean up the whelping box regularly, look for any objects that could possibly damage the mammary gland, and remove them from your dog’s space.

Careful monitoring at home is vital to make sure your dog is responding to treatment and not getting worse. If the antibiotics don’t seem to be working, it is essential to bring your dog for a revisit as a different treatment might be needed.

In moderate and severe cases, your dog may need to be hospitalized for IV fluids and antibiotics to treat the infection more aggressively. Repeated ultrasounds may be required to monitor the progression and resolution of abscesses and cellulitis inside the gland.

If there is an abscess or damage to the mammary gland, surgery might be required to flush out the pus or remove the affected gland.

In cases where milk production is causing a problem, medicine can be given to stop lactation (anti-prolactin therapy).

If there is a tumor, then x-rays, surgery, and chemotherapy or radiation may be required. Other infections in the body will need to be treated, and mastitis if the disease has spread from somewhere else.

What Happens to the Puppies?

In mild cases, the puppies can continue to nurse and may actually aid in the stripping of the affected gland. Nursing from affected glands has not been shown to be problematic for puppies.

There are antibiotics and pain relief that are safe to use in lactating dogs, so most veterinarians will select these first to ensure there are no problems.

If it is determined that an antibiotic is required, that could be detrimental to the puppies, and then they might need to be switched to being bottle-fed while the dam is on the medicine, or they could be weaned if they are old enough.

In dogs in a severe condition, the puppies may need to be bottle-fed while the mother dog is in hospital, but it’s possible that the puppies can go back to nursing once the medicine is finished.

Prognosis and Prevention of Mastitis in Dogs

Mild mastitis cases have a good prognosis, but they can still recur in subsequent lactations despite preventative measures.

More moderate and severe cases can still have a good prognosis as long as adequate treatment is instigated quickly. The outcome will depend on how fast the dog is treated, the type of infection, if there is any antibiotic resistance, and the health of the dog otherwise. Dogs with dying tissue and in septic shock are in a severe condition and may not recover.

Prevention involves good animal husbandry, including high-quality food, and providing a clean and safe whelping area will help prevent mastitis. Ensuring your dog is otherwise well and treating any other infection and illness will make sure their immune system is strong enough to fight infection. It can be difficult to prevent mastitis, so early detection is key to a good outcome.

Early detection through regular weighing of the puppies, temperature monitoring of the mother, and checking the mammary area for signs of heat and swelling will all help to show when there’s a problem so that treatment can be instigated quickly. Expressing the glands twice daily to check the color of the milk and look for signs of pain can also be helpful.

Mastitis can be very serious, but it doesn’t need to be. If you are careful about monitoring your animal and pick up on signs of infection early, a visit to your veterinarian and course of antibiotics will hopefully be all that’s required. If you’re ever unsure about your dog’s health, it’s better to be safe than sorry and get them checked over.

If you enjoyed this article, you could also read our article on Tumors of the Reproductive System in Dogs.