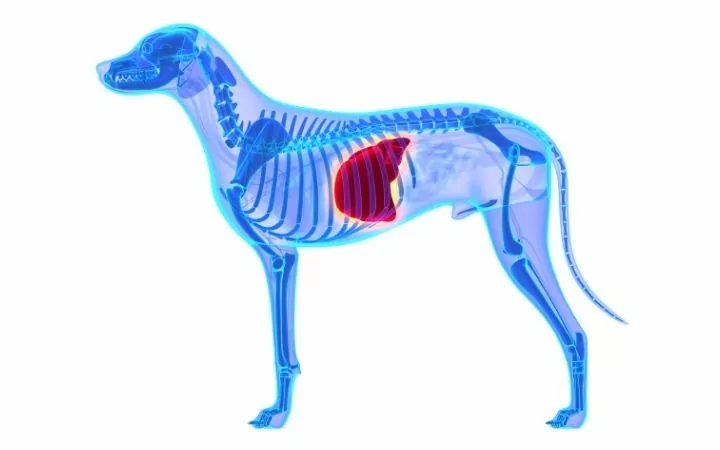

A portosystemic shunt in dogs (PSS further in this article) is a condition that explains an uncharacteristic connection between the systemic circulation of the body and the portal vascular system in dogs and cats. In this article, we will talk about this condition in dogs, as it is rarely seen in cats.

When this condition is present in a dog, the blood from the abdomen’s organs, which should usually be drained in the liver by the portal vein, is instead by-passed or shunted to the new systemic circulation by the portosystemic shunt.

In translation, this would mean that some of the proteins, nutrients, and toxins that are usually absorbed by the intestines will bypass the liver and its circulation and will be “shunted” directly into the systemic circulation of the dog.

Most portosystemic shunts in dogs are considered congenital or that the dog or cat is born with it. A congenital portosystemic shunt in dogs is divided into two categories:

- Intrahepatic (when the shunt appears inside the liver), and

- Extrahepatic (when the shunt appears outside the liver).

Sometimes, under certain conditions, portosystemic shunts can develop secondary to other liver problems such as cirrhosis, chronic cholangiohepatitis, neoplasia of the liver, and arteriovenous fistulas. These portosystemic shunts are known as acquired.

Which Dog Breeds Are Predisposed to PSS?

The genetic basis of a portosystemic shunt is still unknown to veterinarians and researchers. Still, over the decades, scientists discovered that certain breeds of dogs, in comparison to others, are more expected to have this condition.

This does not mean that other dog breeds, or mixed breed dogs, cannot have congenital or acquired PSS.

Dog breeds in which the most cases of PSS are observed include:

- Maltese dogs

- Yorkshire Terriers

- Cairn Terriers

- Miniature Schnauzers

- Irish Wolfhounds

- Golden Retrievers

- Labrador Retrievers

- Australian Cattle Dogs

- Old English Sheepdogs

- Havanese dogs

- Pugs

- Bichon Frisé’s

- Shih Tzu’s

- Jack Russel Terriers

- Border Collies

A congenital portosystemic shunt is usually seen in purebred dogs instead of mixed-breed dogs. Mixed-breed dogs that show symptoms and are diagnosed with canine portosystemic shunt usually have the acquired type that follows another primary liver problem or dysfunction.

Researchers have discovered that congenital portosystemic shunts also vary from the dog’s geographical location, which is due to the genetic and environmental characteristics of the region.

Researchers also discovered that large dog breeds (90%) tend to suffer from intrahepatic portosystemic shunts, and small dog breeds (93%) usually are diagnosed with extrahepatic portosystemic shunts.

The occurrence of inoperable or unusual congenital PSS in dogs is more likely to occur in breeds that are not in the predisposed dog breed list. One possible explanation for this is that the predisposed dog breeds will usually suffer from programmed, expected genetic defects, and the PSS in non-predisposed species probably is a result of random errors in the embryogenesis.

Even though congenital portosystemic shunt is considered inherited, the exact mechanism of this inheritance is elucidated.

Pathogenesis and Hemodynamics

Portosystemic shunts are considered to be abnormal or unusual connections between the portal system of a dog (gastric, caudal, and cranial mesenteric, phrenic and splenic veins) to the caudal vena cava.

When a congenital portosystemic shunt is present, it is the result of a persistent ductus venosus. This is a form of hepatic sinusoids and portal vessels from fetal development.

This is caused by a failure of the fetal circulatory system of the liver to change at birth.

Typically, it is expected that the placenta’s blood bypasses the liver and goes into the circulation through the ductus venosus (fetal blood vessel). The ductus venosus should close at birth.

Failure to do this will result in an intrahepatic shunt. In comparison, extrahepatic shunts result from an abnormality in the development of the vitelline veins that connect the portal vein to vena cava caudalis.

In young and adult dogs with a portosystemic shunt, the intestines’ blood will only partially go through the liver, and the rest will be remixed into the general circulation. This means that toxins such as ammonia will not be emptied by the liver.

Congenital portosystemic shunts in dogs are usually solitary, whereas acquired portosystemic shunts are multiple and caused by portal hypertension.

Acquired portosystemic shunts are usually seen in senior dogs that suffer from cirrhosis but can be seen in younger dogs that suffer from liver fibrosis caused by dissecting hepatitis.

Signs and Symptoms of Canine PSS

Many of the clinical signs and symptoms of a portosystemic shunt in dogs will be the consequence of the circulatory blood not be filtered through the liver. This unfiltered blood will have high levels of toxins that will be sent to the brain and will be toxic to the central nervous system. This will make the dog show variety of neurological signs.

These neurological signs may include:

- Hyperactivity

- Lethargy

- Restlessness

- Incoordination

- Blindness

- Stupor

- Ataxia

- Head pressing

- Seizures

- Coma

- Death

Other general signs may include:

- Impaired development and growth

- Poor muscle development

- Deprived condition

- Anorexia

- Vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Constipation

- Cystitis

- Polyuria and polydipsia (excessive drinking water and urination)

- Stranguria (difficulty urinating)

- Hematuria (blood in the urine)

- Urinary bladder stones (due to increased uric acid in the circulation excreted from the kidneys)

- Excessive salivation (ptyalism) but is more frequently seen in cats rather than dogs.

As you can see, the clinical signs of a portosystemic shunt in dogs are very variable. Most dogs will develop some of these clinical signs early in life, as early as six months of age.

Also, many dogs may have only a few clinical signs and signs that are not very easy to connect with this condition. The clinical signs may also be episodic, which makes the diagnosis very difficult.

Most canine patients with portosystemic shunt will show a history of generally doing poorly. Many of the dogs will be small for their age and will show bizarre behavior.

These dogs will also show very poor tolerance to sedatives and anesthetics. Radiographs may also show incidental findings of a small liver. Many of the dogs will show the occurrence of neurological clinical signs after eating a high protein meal.

The Causes of Portosystemic Shunts

As we learned, portosystemic shunts in dogs are either congenital or acquired. Congenital portosystemic shunts are caused by a persistent ductus venosus or a ductus failure to close at birth.

This will result in an intrahepatic shunt. Extrahepatic shunts result from multiple abnormalities of the development of the vitelline veins that connect the portal vein to vena cava caudalis.

Acquired portosystemic shunts in dogs are most commonly the result of primary liver diseases such as cirrhosis or liver hypertension. This type of portosystemic shunt is usually seen in older dogs and any dog breed.

Diagnosing PSS

Diagnosing a portosystemic shunt in dogs can be quite challenging because of the many varieties of clinical signs and symptoms.

If your veterinarian suspects that your god might have a portosystemic shunt, be prepared for an extensive diagnostic work-up. Some of the diagnostic tests may be conducted by the primary veterinarian, but many cases are referred to a veterinary specialist.

In dogs with suspicious clinical signs, the veterinarian will perform several blood tests:

Complete blood cell count

The complete blood cell count might show a mild microcytic, normochromic non-regenerative anemia, poikilocytes, and target cells.

These abnormalities are considered to be the result of iron sequestration, iron deficiency, and the abnormal metabolism of lipids.

Biochemistry profile

The biochemistry profile usually does not show elevated liver enzymes, but some dogs that are suspected of PSS might show elevated ALT, AST, and ALP. Dogs suspected of portosystemic shunt will show hypoalbuminemia, hypocholesterolemia, decreased BUN, hypoglycemia (especially after fasting), and increased serum bile acid concentrations due to poor liver function. Bile acid concentrations are measured after fasting and 2 hours after a meal.

When measured, in healthy dogs, fasting bile acids are 5-15 µmol/L, but in most dogs with a portosystemic shunt are higher than 25 µmol/L.

Bile acids measured after 2 hours of a meal in dogs with a portosystemic shunt are higher than 75 µmol/L.

A study showed that healthy Maltese dogs have deceptively elevated bile acids because of a chemical that can interfere with spectrophotometry.

Urinalysis

The urinalysis will show low specific gravity and the presence of ammonium biurate crystals.

Liver biopsy

If a liver biopsy is performed, it will show signs of atrophy, decreased number of portal tributaries, and a proliferation of the arterioles and the bile ductules.

Radiographs

On plain radiographs, without a contrast, we may see a small liver. Some dogs with portosystemic shunts may have enlarged kidneys or the presence of calculi in the kidneys and/r the bladder (urate or struvite stones).

Ultrasound

Ultrasound can be a useful tool for detecting a portosystemic shunt in dogs. Still, you will need a high-quality ultrasound machine and an ultrasound specialist with a much-trained eye.

Intrahepatic shunts can be easily detected via ultrasound because they are very large.

Sometimes, if the shunt can’t be visualized on the ultrasound, other signs can be seen, such as enlarged kidneys and sediment in the kidney and the bladder. When there is a congenital portosystemic shunt, a decreased portal vein can be visualized, and a very turbulent blood flow.

There is another method for detecting shunts via ultrasound and includes injecting agitated saline solution into the spleen and ultrasound the distal vena cava or the right atrium searching for air bubbles.

Portogram

A portogram is a handy diagnostic tool for detecting portosystemic shunts in all animals. It requires injecting saline, radio-opaque, water-soluble contrast solution into a catheterized splenic or jejunal vein (2ml/kg is the maximum dose).

After injection, radiographs are taken every 1-3 seconds or continuously if a fluoroscope is used. If a shunt is present, it will show very distinctively.

Nuclear scintigraphy

For this procedure, the injection is performed directly into the spleen and provides a portogram in some animals. Around 70% of the cases allow accurate differentiation between a single congenital portosystemic shunt and multiple extrahepatic shunts.

After this procedure, the animals are radioactive, and because of this, the veterinarian will ask for the dog to spend the night at the hospital.

Surgical Techniques

When a portosystemic shunt in dogs is diagnosed, the preferred treatment option is surgery. For surgery to be performed, the patient first needs to be stabilized, so dogs undergoing seizures because the shunt first needs to be medicated because otherwise, they will not survive the surgery.

For solitary congenital shunts, the goal of the surgery is the regeneration of the hepatic tissue by returning the hepatic blood supply and to prevent further liver fibrosis and atrophy. For this surgery, an experienced veterinary surgeon is required.

Extrahepatic shunts (and some intrahepatic shunts) can be fixed by inserting aneroid constrictors (stainless steel ring with an inner caseous core) or cellophane bands on the azygous vein or vena cava caudalis.

When the ameroid constrictor is inserted, the core will absorb the abdominal fluid, and it will swell and will cause a fibrous tissue reaction. This will cause to close gradually over two to four weeks.

In some cases, if the ring is too small or too loose, portal hypertension might develop. The cellophane bands work similarly to the ameroid constrictors, causing fibrosis of the shunt. The cellophane band should also be larger than the diameter of the shunt to avoid portal hypertension.

Intrahepatic shunts can be treated with surgical ligation of the hepatic vein, which will drain the shunt or the branch supplying blood to the shunt, ligation of the shunt itself, intravascular occlusion of the shunt, or embolization coils. With ligation, there is an increased risk of hepatic congestion and severe hemorrhage.

Prognosis

After the placement of aneroid constrictors or cellophane bands, 85% of the dogs become clinically normal and healthy within four months of the surgery.

Intrahepatic shunts will have a higher mortality rate due to the surgery’s difficulty (5-25%).

Lower mortality rates are seen with coil embolization, but the dogs need to be kept on gastroprotective medication for their entire life.

In dogs with partial shunt ligation, there is a recurrence of clinical signs after three years of the surgery. Many of these dogs will develop multiple PSS.

Dogs with portosystemic shunts, before and after surgery, will have to undergo a diet change. This means that they will need to be placed on a diet regime with low protein and high fiber to reduce the number of toxins absorbed through the intestines.

The dogs should be given lactulose daily to change the intestines’ pH level and decrease the absorption of ammonia and other toxins. This will create an environment in the intestines that is unfavorable for toxin-producing bacteria.

Conclusion

A portosystemic shunt in dogs is a severe life-threatening condition that requires a series of tests and surgery to be resolved. Many dogs might go undiagnosed because of the randomness of the clinical signs and symptoms.

Portosystemic shunt means that there is an extra set of veins in the hepatic circulation. The blood from the circulation that needs to be filtered through the liver is bypassed and thrown back into the systemic circulation.

This means that the toxins are not filtered and are in the bloodstream again, causing various neurological, gastrointestinal, and many other symptoms.

The preferred way for “fixing” the shunt is surgery, and most dogs live a happy and healthy life afterward.